A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

New Sources on NATO Enlargement from the Clinton Presidential Library

Documents from the Clinton Presidential Library can facilitate new interpretations of NATO’s open door-policy and its implications for the emergence of the post-Cold War order.

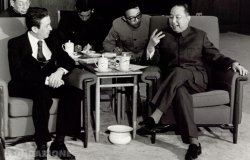

President Clinton and President Yeltsin, October 23, 1995, Hyde Park, New York, image by Ralph Alswang. NAI #596517, William J. Clinton Library.

To date, the scholarly debate on NATO enlargement has largely focused on Russia and the end of the Cold War. Newly declassified sources from the Clinton Presidential Library, however, facilitate new interpretations of NATO’s open door-policy and its implications for the emergence of the post-Cold War order.

NATO enlargement was not purely about Russia. The newly released Clinton files suggest a broader agenda. Namely, the transatlantic beliefs that the end of the Cold War did not solve Europe’s security issues, and that NATO had to reinvent itself politically for the challenges of the post-Cold War era.

Enlargement was part of the US effort to update and realign the entire architecture of relations between the United States and Europe – a policy welcomed by many Europeans. In 1994, Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl asked the Clinton Administration “to increase its involvement in the ongoing effort to chart the future of Europe…EU enlargement, an EU defense component and NATO expansion can all be made compatible.”

Initially, the Clinton administration was divided between Russia firsters and Russia skeptics. Russia-firsters were concerned that NATO enlargement would aggravate Russian insecurities; Russia skeptics supported enlargement because they believed NATO needed to capitalize on Russia’s temporary weakness.

The emergence of the Partnership of Peace (PfP) was a compromise between both camps. Its purpose was to enable the former Warsaw Pact countries and the post-Soviet states to build up individual relationships with NATO, based on their own individual priorities.

The PfP intertwined containment and engagement. In January 1994, Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Clinton’s Russia adviser Strobe Talbott argued that “one of the best things about PfP was that it could go in either direction: it could lean forward to accept Russia if the ‘good bear’ emerges, but could also lead to a post–Cold War variant of containment to confront a post–Cold War variant of Russian expansionism.”

Policymakers in Central and East Europe were disappointed about PfP’s phased approach, and saw it as an endless waiting room before their full article 5 NATO membership. They sought security in NATO, as they feared a potential return to authoritarianism in Russia, particularly after Russia’s constitutional crisis of 1993 and the stand-off between President Boris Yeltsin and the Russian parliament.

Even prior to the autumn 1993 events in Russia, Polish President Lech Walesa told Bill Clinton that “it is possible that the reform process in Russia will reverse. This would spoil the progress that has been made in building peace in Europe…If you succeed in ensuring that Europe is not again faced with a threat from Russia, you will win a Nobel Prize.”

PfP signaled that NATO pursued a policy of two tracks: the aim was to open up NATO, but slowly and cautiously, and combined with an expanded effort to engage Russia. Clinton emphasized repeatedly that Russia was not excluded from NATO and would be eligible to join the alliance someday.

Yeltsin, on the other hand, did not want Russia to be treated as just one among the many PfP countries. He insisted on “a statement or ‘protocol’ that makes clear that Russia is different from all other countries joining PfP – ‘a great country with a great army with nuclear weapons.’”

In December 1994, the Clinton-Yeltsin summit in Budapest turned into a confrontation after NATO’s Foreign Ministers had used their December 1994 meeting to accelerate the enlargement process. Yeltsin asked Clinton for a better understanding of what NATO was doing, “because now I see nothing but humiliation for Russia if you proceed [with enlargement]. How do you think it looks to us if one bloc continues to exist while the Warsaw Pact has been abolished?”

Western policymakers believed in their own ability to bring Yeltsin around on the NATO question. In 1995, Clinton and Yeltsin started discussions about a set of special NATO-Russia relationships that culminated in the establishment of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997. Its purpose was to formulate a charter on NATO-Russia cooperation in an effort to give Russia a place in an inclusive security community in the Euro-Atlantic area.

The Clinton files are also revealing of another NATO challenge: who would become a new member, and when. The Alliance had intense debates about the timing of enlargement before agreeing that Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary would become members in 1999.

Questions about the pace of enlargement had an important psychological dimension. The young democracies in Central and Eastern Europe wanted to be part of “a Europe whose institutions covered the same territory as the Europe of the map,” as Richard Holbrooke put it in a conversation with Romania’s President Ion Iliescu in 1995.

Germany and France were particularly cautious, arguing that a strong open-door package was sufficient as a reassurance. In 1997, with regards to Romania, for instance, Germany’s President Roman Herzog told Bill Clinton that “the conclusion I draw is that we did the right thing in not inviting them to join NATO just yet. Their per capita income is less than one-half of Poland's. To meet their military responsibilities in NATO, they would need to spend five or six percent of their GDP. They should not do that at this point.”

Last but not least, the newly declassified sources from the Clinton Library include documentation on the modification of NATO’s modus operandi and its efforts to engage militarily “out of area,” manage crises, consider peace enforcement missions and undertake humanitarian interventions.

In particular, the war in Bosnia signaled that history and old conflicts had the potential to upset NATO’s order-building diplomacy and the emergence of a peaceful and prosperous Europe. In February 1995, Helmut Kohl told Bill Clinton that “with respect to Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, NATO expansion, and the status of Ukraine, these are the essential points. No matter what we do with Moscow, if we fail in Ukraine (and the former Yugoslavia) we are lost...The situation in Europe is very vague and ambiguous.”

Research on NATO enlargement is politically relevant for the security debates that have been ongoing since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea. Is there a new Cold War? Or are we still grappling with an unfinished post-Cold War settlement?

The Clinton files gives us a better understanding of the current crisis in NATO-Russia relations and new insights into the post-Cold War challenge to find Russia a place in the new world order. Thus, the Clinton files connect post-Cold War history with twenty-first century politics.

About the Author

Stephan Kieninger

Independent Historian

Stephan Kieninger is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center and a historian of transatlantic relations since the Cold War.

Read More

History and Public Policy Program

The History and Public Policy Program makes public the primary source record of 20th and 21st century international history from repositories around the world, facilitates scholarship based on those records, and uses these materials to provide context for classroom, public, and policy debates on global affairs. Read more

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Through an award winning Digital Archive, the Project allows scholars, journalists, students, and the interested public to reassess the Cold War and its many contemporary legacies. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more