The Iranian regime celebrated, on February 11th, the forty-fifth anniversary of the Islamic Revolution. Three weeks earlier and after a year of massive protests in 1979, the Shah had left the country. On February 1st, Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution, returned from exile to be greeted by millions. The euphoria was universal, and women were part of it. Women expected a new dawn—an acceleration of the process initiated under the monarchy that would now culminate in full equality under the law. Disappointment was not long in coming. As the historian Shaul Bakhash put it regarding his enthusiastic friends, “[they] loved the revolution, not knowing it would not love them back.”

In their excitement, women did not notice that the revolutionary council and new government that was quickly put in place to run the country did not include a single woman among their members. Nor did they anticipate what followed. Women had expected a rapid expansion of their rights. The clerical leaders of the revolution, on the contrary, aimed to undo the rights women had secured under the monarchy. They sought to return women to their traditional roles as homemakers and mothers. But as they confidently set about to put in place a new regime that would govern women’s lives, they did not anticipate in their wildest dreams that women would put up a stiff resistance.

For the last 45 years, women have remained a thorn in the side of the Islamic Republic and its clerical and non-clerical officials

Women's rights decline

For the last 45 years, women have remained a thorn in the side of the Islamic Republic and its clerical and non-clerical officials, and their focus has been on access to education and work, presence in the social space, and freedom to choose for themselves.

It didn’t take long for the hijab to be imposed on women. Within months, the Hijab became the official attire of the Iranian women, first in government offices and then across the board. (The Hijab, along with a mandatory loose, long robe in dark colors, was supposed to reflect the chastity of women). But women came out in their thousands to protest. Much else followed.

A gradual purge of women from decision-making positions in the public sector took place, depriving women of the opportunity to earn a living. Where women remained at work, they were not permitted to share the same office with their male colleagues. Male teachers could no longer teach in girls’ schools, and since math and science courses were taught primarily by men, this meant young girls were denied training in the science fields. At universities, women and men were separated in classrooms, men and women could not mix on campuses, and women were entirely barred from certain fields of study.

One of the most drastic measures taken was the suspension of the Family Protection Law. Passed under the monarchy, the law raised the age of marriage for women, gave women the right to seek divorce and child custody rights, and set up family courts to ensure fair treatment in family disputes. With the suspension of the law, women lost the right to sue for divorce, the age of marriage for girls was reduced from eighteen to nine, child custody was automatically granted to the husband, and the family courts were abolished. Moreover, women were barred from serving as judges in any court in the justice system.

Armed men who patrolled the streets were authorized to ensure men and women who appeared in public or in a car together were related as husband and wife, brother and sister, or father and daughter. Otherwise, punishment followed. True, women could still vote and be elected to parliament, but the handful of women who were elected were, with few exceptions, silent regarding the repression to which women were now subjected.

Gradually, women began to push back and make use of small windows of opportunity.

Women fight back

Gradually, women began to push back and make use of small windows of opportunity. They wrote letters to the office of Ayatollah Khomeini and other government clerics, lodging complaints and demanding restitution of their lost rights. With tens of thousands of young men at the front during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), the government was forced to employ more women to work; they became the sole breadwinners in the family. In cases where a father died fighting in the war, the newly reconstituted family courts were inclined to give the child custody to the mother rather than the immediate male relatives of the father.

Women waged a persistent’ battle of the hairline’, pushing back their headdresses to show more and more of their hair. The hemline of the ‘manteau’—the long robe all women were required to wear—gradually grew shorter. Much to the consternation of some parliamentary deputies, in national university entrance examinations, more women consistently won university entrance than men. A much larger number of women entered the workforce; and many women began to launch small businesses in the private sector or started businesses from home.

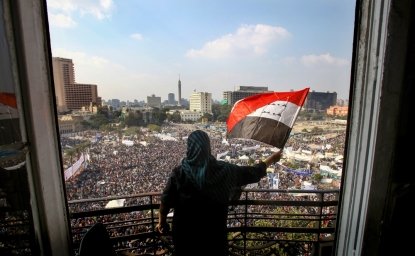

Women have also been prominent in the major protest movements of the last 45 years. These include the massive protests in 2009, when President Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad was elected to a second term in a rigged election, and support for school teachers, government employees, and workers protesting due to unpaid salaries. Like many others participating in these demonstrations, women paid dearly, suffering beatings, arrests, imprisonment, and even torture and rape.

In 2023, when a young woman, Mahsa Amini, was arrested for violating the Hijab and died in police custody, thousands of women poured into the streets of Tehran and other cities. Most removed their Hijab, and some even burnt their scarves in solidarity with the dead Mahsa. These protests launched a movement, “Women, Life, Freedom,” that became a rallying cry for both women and men and resonated worldwide. As always, the government remained deaf to women’s demands. Parliament even passed a stricter hijab law. Among other provisions, security officers were authorized to confiscate the cars of women driving without their headcovers. But women have continued to challenge the new law, and there are signs the government is relenting. To mark the 45th anniversary of the revolution, the government announced last week it is returning to women their impounded cars. We shouldn’t be surprised if the women showing up to claim their cars will not be wearing the Hijab.

It is a mark of the courage of the women of Iran that twice in the past forty-five years, an Iranian woman won the Nobel Peace Prize: Shirin Ebadi, the human rights lawyer, in 2003, and Narguess Mohammadi, a fearless defender of women’s rights, in 2023. The resistance will not soon end; and, as evident from the many young men who joined the women protestors in the Mahsa Amini demonstrations, this is a struggle for rights and freedom that will be waged by both women and men of Iran’s younger generation.

The views expressed in these articles are those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the Wilson Center.